By Emma Love

This article first appeared in our September/October 2016 issue.

This article first appeared in our September/October 2016 issue.

In a technological world where business takes place at the click of a button, it’s easy to forget that commerce was historically all about shipping goods vast distances by horseback. Emma Love steps back in time to learn about a remote region of China where the export of tea was once a way of life.

Once the longest trade route in the ancient world, the Tea Horse Road stretches across 2,485 miles of mountain trails in China’s south-west province of Yunnan. The trails were used to transport the coveted Pu-erh tea, which is only grown here, and which, in its rarest form, once fetched $1.7m for four-and-a-half pounds in a 2013 auction. Carried by mules from the trading post town of Lijiang to Lhasa, the tea was exchanged for Tibetan medicine, spices, salt and leather. It was an arduous journey for the ethnic Naxi people, who led their squat, robust mules for several months over rough, dangerous mountain terrain, winding through tiny towns, such as Benzilan and Adong, towards Tibet.

My own considerably shorter journey to learn more about the Tea Horse Road begins in Chengdu, the capital of the Sichuan province and home to 14 million people. The traffic-jammed streets and designer fashion stores of the Taikoo Li district make it hard to imagine that one strand of the trail once ran through here. The district is partly owned by Swire Hotels which last year opened its third outpost, Temple House, that cleverly combines restored Qing dynasty buildings with slick contemporary interiors. It also has an excellent Mi Xun teahouse and spa, and the Jing bar, which is packed with locals sipping tongue-tingling Sichuan Mule cocktails at night.

I wander through Wide Alley and Narrow Alley, formerly home to high-ranking military officers from the Chinese army, which are now two criss-crossing pedestrian shopping streets, where food stalls sell snacks, such as pineapple rice and rabbit heads. On one side of the alley, a man lies back in a dentist’s chair to have his ears waxed for 60 RMB (about $9). It has a similar vibe to Lijiang’s Old Town (a designated Unesco World Heritage site), which I discover after a two-hour flight the next day. An earthquake in 1996 meant that much of the area had to be rebuilt, but it has been carried out in a sensitive way that is utterly charming. Red lanterns hang from rows of little shops – selling Buddha beaded bracelets, rose flower cakes and colorful cotton scarves – along cobbled streets filled with bridges.

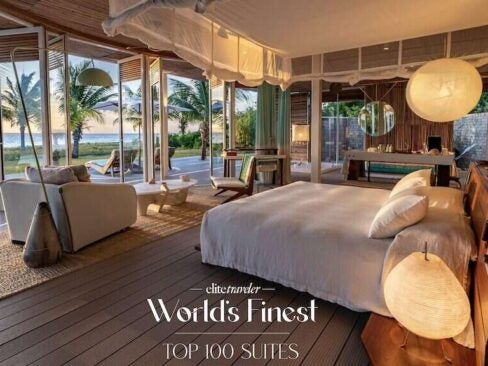

LUX Lijiang, the first in a planned string of hotels to line the Tea Horse Road

And since last year, there’s also LUX Lijiang, the first in a planned string of eight to 10 hotels from the LUX Resorts & Hotels group to line the Tea Horse Road by 2021 (the second property, LUX Benzilan opened in December). Tucked away on the quieter south side of the Old Town, the LUX Lijiang’s 10 rooms each have pine floors and furniture. On the walls hang black-and-white images related to the Tea Horse Road by photographer Michael Freeman (who has produced a book on the subject, Tea Horse Road: China’s Ancient Trade Road to Tibet). The marble bathrooms, which come with a round copper sink, are stocked with roseroot scented Tibetan bath products. There’s a tea table in the lobby, where a welcoming cup of tea is poured for new guests, a small library upstairs and a few outside tables that are the perfect spot for a bowl of breakfast noodles.

Over the next couple of days, I visit the nearby Baisha village, another original Naxi settlement that’s now part of the Lijiang, where 94-year-old Dr Ho (whose claims to fame include appearing on Michael Palin’s British TV travelog Himalaya) has run a clinic offering free traditional herbal medicine since 1985. Armed with a canister of oxygen, I take the cable car up Jade Dragon Snow Mountain to an altitude of 14,783ft where a bride in a red dress braves the snow for a pre-wedding photo shoot. Finally, I watch the Impressions of Lijiang performance directed by Zhang Yimou, who was the mastermind behind the opening Beijing Olympics Opening Ceremony. The brilliant hour-long outdoor show, which is performed by 500 local farmers with the mountain as a backdrop, tells the story of the Tea Horse Road and the life of the minority of people who walked the trails. The highlight is 100 red-caped caravan chiefs riding around the ring on horses, whooping and waving their hats.

Next I meet Diana He, owner of the Fu Xing Chang tea house in the Old Town, who talks me through the Pu-erh tea-making process. A tea master weighs the leaves out to exactly 12.5oz, steams and then flattens them into a round cake by standing on a wobbling stone weight. “Pu-erh tea was cheap and unlike other teas it could be stored for long periods of time. It also contains the lowest amount of caffeine of all teas so it can be drunk all day,” says Diana, explaining why the Tibetans liked it so much. “In Tibet, people eat a lot of meat and the tea helps with digestion.”

Baoshan Stone Village clings to the sides of a massive rock

The next day, I get the taste of a typical Tibetan diet when I head north to Shangri-La for lunch: yak hot pot, baba bread and yak butter tea, which is seriously salty. The houses here feel more Tibetan too, with cream adobe walls, intricately carved wooden window frames and racks in the garden for drying hay. After a wander through the mostly deserted town in the pouring rain I carry on, driving north, past fields of barley, wandering cows on the road and wetlands where the only sound from grazing horses is the jingle-jangle of their bells in the wind, until we reach LUX Benzilan.

The town itself is one of the last in Yunnan before the Tibetan border and the delightful 30-room hotel is right next to the Yangtze River. Interiors are carefully considered and full of local touches, from the cluster of handmade black clay lights made in the nearby pottery village of Nixi that hang in the lobby to the original wicker baskets and horse bells once used by the mule-drivers, which were bought from the Ancient Tea Horse Road Museum in Shuhe, near Lijiang, and are now housed in the library. Guests can immerse themselves in local experiences, which include learning how to make traditional yak butter tea, visiting the nearby Dong Zhu Lin monastery where the monks chant for two hours in the courtyard every morning, stopping for pictures at the famous first great bend of the Yangtze River, to retracing the steps of the mule-drivers on a four-mile guided hike through Haba Snow Mountain on an original Tea Horse trail. The dinner at LUX Benzilan, Sichuan-style steamed fish, amazing wine-braised chicken, spicy potato slices, is the best food I taste on the entire trip.

A friendly wave from a local

The next day I decide to try and get a glimpse of the Meili Snow Mountain further north. It’s the highest in Yunnan and sacred to Tibetan Buddhists. No one has ever managed to reach the summit and now even attempting the climb has been banned. A light dusting of snow becomes almost instantly thicker as the driver takes the winding hairpin bends, climbing higher and higher. The landscape is magical – although the sheer drop feels perilously close and is pretty hair-raising. Suddenly there’s a traffic jam as several trucks full of pigs get stuck up ahead. I take the opportunity to jump out and take pictures of the snow-covered spruce trees that carpet the mountain. At the 14,000ft mountain pass, where colorful flapping prayer flags are tied like bunting to a chorten (a Buddhist place of worship), I meet a young vacationing couple on an epic 12,400-mile trip by car to Beijing that takes in part of the Tea Horse Road. As I get closer to the village of Feilaisi, usually a good vantage point for Meili, the fog closes in and I only catch a glimpse for a few seconds before it disappears. No matter, we carry on instead to our final destination – the remote village of Adong, population 120, just over 27 miles from Tibet’s border. Until a few years ago, it could only be reached by a bone-jarring dirt track.

This region was put on the map by early 20th-century Victorian plant hunters who came to the valleys to collect specimens of rhododendrons and Forrest’s tutsan, but it’s only now that there’s a sense of change slowly happening in the village. In 2013, Moët Hennessy opened a winery as part of China’s burgeoning future as a world-class wine producer. Tibetan farmers were persuaded to switch from barley and walnuts to vines on the terraces that are flat enough for cultivation, and now wine connoisseurs eagerly await the winery’s first release, the 2013 Aoyun vintage. I have lunch at the home of village doctor Suo Nan, who practises a mix of traditional Tibetan, Chinese and Western medicine. As I tuck into a feast of mushrooms (about 800 of the world’s varieties of mushrooms are found in Yunnan), pork, stir-fried vegetables and omelette with bitter gourd, he tells me about the mountain trail that runs from here to the next village of Diqing.

Since the proper road was completed a couple of years ago, Suo Nan says that the trail is hardly used anymore and motorcycles have replaced horses as the most popular form of transport. Before I leave, I decide to walk up the road to the entrance of the trail where, sure enough, after only a few minutes, a motorcycle zooms down. Then, just as I start to turn away a horse appears, being led by its master, passes us and is off along the road. Seeing a horse still using one of these ancient trails feels like a fitting end to such an extraordinary trip in this remote part of the world.