He went from being a director of music videos and a celebrity photographer to becoming one of the most renowned and record-setting polar explorers of our day.

Sebastian Copeland is also an award-winning nature photographer and activist who fights to bring awareness of the climate crisis to the forefront. Here, he shares his stories with Roberta Naas.

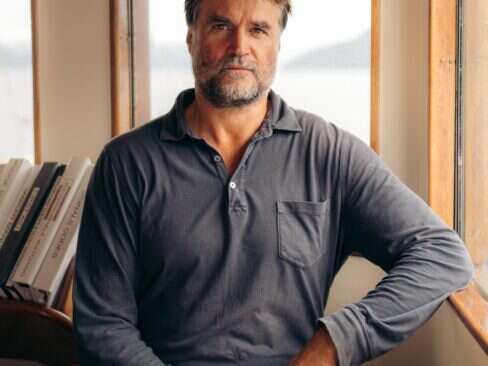

Some might call him a Renaissance man. Moving from the fast-paced world of shooting album covers and celebrities to becoming an explorer, nature photographer, director, author, lecturer and passionate environmentalist, Sebastian Copeland is somewhat of an enigma.

In just one conversation with him, topics range from the ever-changing northern and southern landscapes to polar bears and paleontology. Somewhat of a scientist (often referring to numbers and scientific studies) and somewhat of a philosopher (commenting passionately about the meaning — and brevity — of time and life), 55-year-old Sebastian Copeland talks more about climate change than he does about his world records and polar explorations.

Still, his journeys have taken him on numerous expeditions across the North and South Poles. He was the first to complete the grueling trek from the eastern to the western coast of Antarctica, and he holds the record for kite skiing the longest distance in a 24-hour period, which took him nearly 370 miles across Greenland.

On that perilous journey, he made the conscious decision to continue, despite recognizing that frostbite was setting in — ultimately losing a portion of his toe. On other journeys, he fell through the ice into sub-zero waters, was battered by brittle ice during whiteouts and came face-to-face with a hungry polar bear.

Copeland has come face-to-face with hungry polar bears

“Operating in this hostile environment means you need to be hyper-focused and aware. In some instances, the line between life and death is razor-thin, and sometimes you need to make tough decisions,” says Copeland. “But it is a dream to be afforded the privilege of the introspective examination that comes with venturing into vast, untouched landscapes that recall another planet. I am greedy for those experiences. There is nothing quite like feeling like you are the last human on Earth.”

Copeland documents the changing landscape of the incredibly hostile polar environment via photography and video. He created the documentary film Into the Cold that followed his two-month journey across 400 miles of the North Pole to commemorate the 100-year anniversary of Admiral Robert Peary’s trip there, and later published the book, Arctica: The Vanishing North. All of his journeys and subsequent articles, books, studies and exhibits reinforce his deep desire to showcase the rapidly disappearing polar ice caps.

“I believe that he or she that walks the land tends to become a warrior in its defense,” says Copeland. “It’s hard not to be moved by nature and not want to be a part of preserving it in some form. For me, conservation is a natural extension or byproduct of my exploration.”

For Copeland, who took his first landscape pictures at the young age of 12 while on safari with his grandfather, photographing ice is similar to photographing people. “I don’t look at the ice caps as inanimate objects, I look at them more as individuals; I look for the way the light strikes them at their best angle,” he says. “I think there is a life cycle to the ice that makes them individuals; they’re born, they travel and they die just like we do.”

Copeland describes being in the Arctic as transcendental, introspective and, in some instances, treacherous. He talks about his very close encounter with a polar bear on the attack and his difficult decision between snapping photos and picking up a gun. In the end, he was able to do both. He got the photos and also was able to scare it back by firing repeated shots into the ice and puddles in front of the bear.

Copeland describes being in the Arctic as transcendental, introspective and treacherous

“Unless you have been in combat, very few of us have faced someone who wants to take your life away. That affects you, the hidden nature of life and what it means to hold onto it. This gives you great pause,” says Copeland. “But this is what drives you. These experiences, the powerful emotions, thinking about what could have happened and how outcomes could have changed. It’s the adrenaline that drives you. It is not for everyone.”

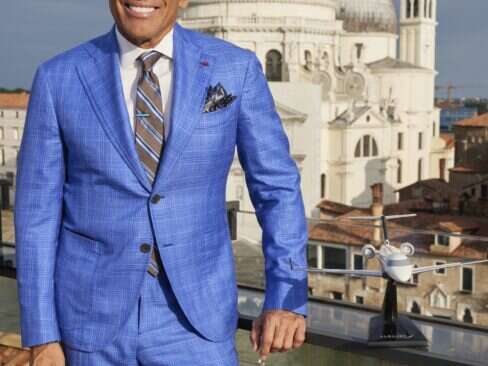

Copeland recently became a brand ambassador for Swiss watch brand Ulysse Nardin, which has created a high-tech dive watch that pays tribute to his treks across the Earth’s polar caps, called the Diver X Antarctica.

“I don’t expect a watch company to be too green, but they care about their footprint and try to follow a carbon-free and conservation path,” says Copeland, who visited the manufacture in Switzerland.

He says that becoming a brand ambassador is a good fit for him because time plays a big role in his life. “Because I am greedy for life’s experiences, there is never enough time to do everything, and when you do something well, it is at the expense of something else. Even though the singular purpose of a camera is to freeze time in an increment, you can’t,” says Copeland.

“Also, when I think of time, I think about humanity. In a time scale, we have barely even existed as humans, and there is a likelihood that we will be gone in a few more seconds, because that is the nature of things. There has not been any species that has survived the cycle of time. These are the thoughts that go through my mind when I am alone on the ice.”

Having spent the past 20 years as an award-winning photographer and adventurer, Copeland insists that he is a man built on three pillars. “The pillars of my house are three things: I live on advocacy, exploration and photography. That’s what defines me, and all of them fulfill a common goal, which is to define me as an individual, or maybe the other way around: me as an individual, and I am there at the service of those three causes.”

However, spend an hour in quiet conversation with Copeland and you realize that he is, at heart, an instrument of change. “Activism is not a label, it’s a moral contract that is within all of us. We can all be agents of change in the actions we take, the products we purchase and the communication that we orchestrate. What was present in the North Pole when Admiral Peary visited 100 years ago was different when I visited a few years ago, and most likely won’t even exist 100 years from now.”

Photos: ©Sebastian Copeland / sebastiancopeland.com