Chairman and CEONetJets Inc.

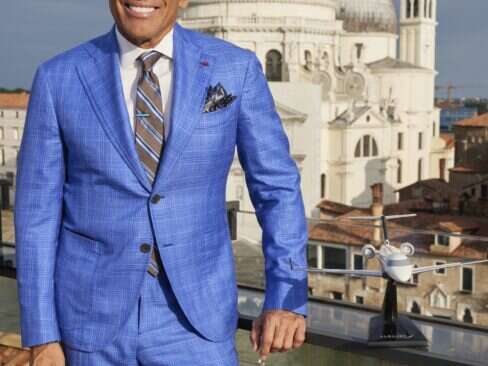

Richard Santulli is often referred to as “the Father of Fractional Ownership,” a concept that helped spur private aviation’s rapid growth over the past two decades. Having founded NetJets, he sold the company in 1998 to Warren Buffet’s Berkshire Hathaway and today, as Chairman and CEO, oversees the world’s largest fleet of 781 private jets from light aircraft to Boeing Business Jets with another 552 on order. With a base firmly established in North America and Europe, and a joint venture operating in Saudi Arabia, NetJets recently announced its intentions to launch in Asia. Elite Traveler Editor-in-Chief Douglas Gollan caught up with Santulli to get his perspective on a wide range of subjects—from working for the Oracle of Omaha, to the future of general aviation, his favorite places for elite travel and other aspects of his fast- growing business.

ET: Can you tell us how you got involved in private aviation and what you were doing before?

Richard Santulli: My prior career was with Goldman Sachs. I ran—I was actually president of—Goldman Sachs Leasing, which is a company we started and which did quite a bit of aviation, leasing mainly commercial airplanes and helicopters. We did all the helicopter leasing that was being done on the Street. When I left Goldman in 1980, I started a leasing company and devoted my energy to helicopters because they were difficult to finance; they were small deals, and as such I wasn’t going to be competing with the big commercial banks, plus I knew all the operators. We became the biggest helicopter lessor in the world. But I also did some airplanes, too, at the same time. We didn’t operate them—we just financed them.

I understood residual values on airplanes and helicopters. In 1984, after being introduced to a company called Executive Jet, I purchased the company. I think we had six airplanes at the time with the commitment to just keep the company in Columbus for ten years, which obviously we’ve done.

One of the major reasons I bought the company was that it was a Bell Helicopter Service Center, which would help me to maintain some of my helicopters. I also had some jets in my lease portfolios, so I figured when those airplanes came off lease, I could put them into a charter fleet, neither of which I did in the long run. Then, at the end of 1986, we started NetJets.

ET: It took a while for the concept of fractional ownership to really catch on. Can you tell us a bit about the early days and some of the challenges?

Richard Santulli: When you think about it, we were basically saying you’ll buy an eighth of an airplane or a quarter of an airplane and we’re going to guarantee you unconditional availability. It was entirely different; people said it was timesharing. Actually, it was just the economics of timesharing but you could use the asset whenever you wanted to.

People thought I was crazy. They’d say, “What happens if all eight people call for the airplane at the same time? How would you guarantee service?” My background is mathematics, so I did the math and created the model. The nice thing about Executive Jet when I bought it is that it had been formed 20 years before and was run by mostly military men. As such, they had kept every record of every single flight that they took for 20 years. So I had a database, which showed that the people in 1984 flew exactly like the people in 1978. Actually, they fly the same today. I knew when they flew, what times of day they most often flew, and I was confident that the math worked.

Was it difficult? Sure. Early on, I did business with people who trusted and knew me. My background at Goldman Sachs helped obviously. Our goal was to initially sell four airplanes a year, which is what we did. Then the recession came in 1990, and we sold an eighth of a share in those two-and-a-half years. I lost, I don’t know, $30 some-odd million because I had basically guaranteed everything personally. So it was tough…very, very difficult.

What happened for those two years is that anybody who had an airplane, number one, they couldn’t even sell it much less make money on it. Fractional then became something that people started to say, “You know, it makes economic sense.”

Unless you fly 400-500 hours, it’s extremely expensive. People had to look at the economics without saying, “I’m going to make money on the asset.” The biggest savings is that instead of paying 100 percent, you’re paying one-eighth. And it’s worked.

ET: You’ve established NetJets as the leader in the fractional space. What are some of the challenges of being in the top spot? How do you feel about the competition you now face as the leader?

Richard Santulli: The first thing is the biggest competitor we have is complacency. We like to have competition. Every day we try to make today better than yesterday. We think we’re the…if not the highest luxury brand in the world, pretty close to it, and what we do is provide the safest operation in aviation while providing our customers with an owner experience that is second to none.

ET: If you’re the Father of Fractional Ownership, you also might be the Uncle of Jet Cards through your relationship with MarquisJet. Can you tell us how that relationship is benefiting NetJets and how it might evolve in the future?

Richard Santulli: Seven or eight years ago Kenny Dichter and Jessie Itsler came in to see us to talk about doing a jet card business. They had sold their (previous) business to SFX, but what they had was a very unique experiential business, where if you wanted to ride on the zamboni in Madison Square Garden, they got it done. If you wanted to sing the National Anthem at a Yankee game, they did it….and were very good at it. They came and talked about doing Jet Cards with us, and I basically threw them out.

I said, “There’s no way. That’s my brand…”

The next time they came in to see me, I think they came in with two football players and a rap star, and still I wasn’t convinced. Then they came in with a rabbi, and they came in again—we must have had five meetings.

The concept was intriguing and we understood it very well. They were very aggressive young guys who wouldn’t take no for an answer. We tested them and they knew it from day one: you denigrate my brand in any way, the deal’s off.

Obviously, our coming together has been very successful. They’ve grown to be a great brand, a great business. They buy a lot of airplanes from us, and it’s a great, symbiotic relationship.

ET: Can you tell us about your long road to success in Europe and your global intentions?

Richard Santulli: A lot of our competitors were trying to go to Europe and a lot of companies were trying to start up, always announcing that they were going to do something. But they’d try and sell the product before they had any product or an infrastructure. We built an infrastructure because we made a commitment that we were going to be there, because we knew that if you look at Europe overlayed with America, it’s got basically the same population, the same GDP.

The good news about being part of Berkshire and why I didn’t want to go public is answered today by looking at Europe. If we were a public company—if we had gone public instead of being sold to Berkshire-Hathaway, we would’ve had to pull out of Europe, because the market would’ve kept saying, “You’re losing too much money in Europe.”

Well, guess what? Up until two years ago we’d lost about $220 million. Today our earnings in Europe are very significant, and I can guarantee you that our business in Europe is worth a lot more than $220 million. So what people would look at as losses, we looked at as an investment. Anyway, now we have a very successful business. We have 135 airplanes. It will be a 300-airplane company in Europe in the next 5-7 years and we are truly a global company.

ET: Tell us about the changes as you developed Europe. At one point MarquisJet was a separate entity there.

Richard Santulli: I sat down with Kenny Dichter and said, “Kenny, look, first of all, you need to apply all of your resources to America. Here’s the marketplace. You don’t have enough capital; it doesn’t make any sense.”

I said, “Let us buy Europe. We’ll take over the card business there. You, then, can generate business in America.” It was the right move. Just like when people say, “Why aren’t you in China or Brazil?” I give the same reason that I gave Kenny: the fact is, we’re not capital constrained, we’re people constrained. To start up another business, to do it right you need the right people. Why would I take people from America—and a lot of them—when I have my market growth still here? When you look at Europe, I’m just in the infancy stage, so it comes down to devoting your energy to the markets you know you’re going to be successful in.

Now, will we be in the Far East? Absolutely. Will we do it the same way we did Europe? Probably not. We’ll probably start with the card business. You have to start with partners, which is something we don’t generally do.

ET: Back here in North America, how is the recession and economy impacting your business, and what is the feedback from your owners on higher prices and fuel surcharges?

Richard Santulli: If you look at the markets today, the big problem is, obviously, the economy’s not great. Still, there is a lot of wealth in our country. Fuel prices have dramatically changed how much it costs someone to fly one of our airplanes. And that has had an impact on our business, as one would expect. The fuel surcharge that we charge is now almost 70 percent of what the occupied hourly rate is. It’s crazy.

ET: Can you give us some data on whether flight hours are up, even, or down?

Richard Santulli: We’re down year over year. The whole industry’s down probably 10-12 percent. If you looked at the number of shares, we have more shares and more owners, but if you look at same-store sales (owners who have had their shares for more than a year), our numbers are 8-10 percent down, which isn’t terrible.

The interesting thing is that when my guys told me this, I assumed it was because the individual was flying less, which is not the case at all. It’s the businesses, the corporations that are flying less—the individuals are flying the same, which was shocking to me. I thought it’d be the other way around.

Businesses are looking more carefully at what the costs are. They’re probably saying, “Oh, you don’t need to take that trip. Let’s forget about it for a while.” The other day I was with a customer in Lexington, Kentucky, who told me, “I just took the redeye back.” I said, “What?” He said, “Rich, I was by myself, I looked at the fuel and at the cost of flying from California back to Kentucky.” He never would’ve done that previously, but now he actually looked at the cost.

ET: What’s it like to work for Warren Buffet on a day-to-day basis?

Richard Santulli: I talk to Warren a lot and I would say that 80 or 90 percent of my conversations are not business related. I talk to him about everything… about Lehman Brothers, about the economy, and how he thinks (Treasury Secretary) Hank Paulson is doing. I’ll talk to him also about my stuff, about where we are selling Marquis cards, interesting stuff like that. We’ll just talk—about politics, about a lot of different stuff.

I’ve never given him a budget. I’ve never asked his approval for buying a billion dollars worth of airplanes. I’m sure if he disagreed with what I was doing he’d tell me after the fact. But I have a very close personal relationship with him, so it might be somewhat different. But if he believes in you, he leaves you alone. I’m sure if he thought you weren’t doing a good job, he’d do something. But he’s not that way. He just leaves you alone, he really does.

ET: Are there any things that you see in how he manages his businesses that you now apply to how you manage NetJets?

Richard Santulli: No, because he doesn’t manage—really, he leaves us alone. In one respect, I absolutely delegate and I’m not a micromanager. There are certain things that I look at—all the marketing stuff we do, I look at. I make sure the sales price is right, but I let my people do it. I don’t micromanage. He doesn’t micromanage either.

You have to pick good people. And when we haven’t picked good people, then we have to make the decision quickly to say, “You don’t belong here.”

Other than that, integrity. But that’s always the way I was brought up. Warren says, “Don’t do anything that you’re not proud to see in tomorrow’s Wall Street Journal.” And I tell our people, if you cheat on an expense account, that’s stealing money. If you need something, we’ll give it to you.

His management style, the difficult part about replacing Warren—in ten years or whatever it’s been—the difficult part is going to be allocation of capital and his brilliance there. There are a lot of smart guys but this guy, if you think about it, since he’s 11 years old, this is all he does. Whereas you might read a novel or I might read the sports pages. He reads 10K’s.

You ever try reading a 10K? You get a headache. But he reads them, and he reads them. You’re talking about a company; it’s amazing what he knows. So the difficult part is the allocation of capital, not learning the operating businesses because he doesn’t spend a whole lot of time running them. He picks good people and lets them do it.

ET: Are there any “best practices” programs across the Berkshire Hathaway family of companies?

Richard Santulli: We’re doing more of that but initially (Warren) didn’t even want to do that, because he didn’t want to tell people what to do. Yes, we are doing some best practice today. But once again he makes it very clear you don’t have to abide by any of those rules or do anything. The only rule? He wants us to be honest and have tremendous integrity.

ET: Going away from work a little bit, do you have any hobbies?

Richard Santulli: I have horses, thoroughbreds. I own a big breeding operation. I’ve got a pretty young family, so I spend a tremendous amount of time with them, and I play golf. And that’s enough.

ET: Are you a good golfer?

Richard Santulli: No.

ET: Handicap?

Richard Santulli: 15.

ET: Okay, that’s good compared to me. What about traveling for pleasure?

Richard Santulli: Flying privately is very expensive; we all understand that. But people that are wealthy that can afford it, especially if you have a family—I have three kids, three dogs—I get on an airplane and I go. And, believe me, I wouldn’t do it commercially. I wouldn’t even go anywhere. NetJets makes traveling easy. That’s what we sell, and I know it’s safe.

ET: Do you travel a lot on business?

Richard Santulli: I go to Europe every six weeks. My business travel is Europe, Columbus, Ohio (NetJets Operational Headquarters), and once in a while to the West Coast to just reconnect with customers, or if we’re having a big event, like the Wynn Poker Tournament.

ET: And when you go to Europe is it all over Europe or any place?

Richard Santulli: London’s my main operation then Lisbon, Portugal is my “Columbus” (of Europe). Every third trip, the sales team will put together meetings—I’ll go to Germany, I’ll go see customers wherever they happen to be.

ET: Are there any particular hotels you like when you’re staying on business, or things that you look for when you’re staying at a hotel?

Richard Santulli: It’s really interesting. We’re going to do a deal now with the (Four Seasons) George V in Paris. They’re going to become our NetJet’s home away from home. We’re going to announce a special relationship with them. In London, I stay at Claridge’s. I love it, and I got accustomed to it. People say, “Why don’t you try a different hotel?” I say, “Why? I’m used to it, they treat me very well, they know me.” I’m a creature of habit, and I love it. It’s a great place. In Lisbon I stay at the Four Seasons.

ET: You sound easy to please.

Richard Santulli: I am very easy to please. I’m in the service business so I know when people care about you because we care about our customers. But sometimes everything can’t be perfect. I get some customers obviously that can be very demanding, though most of them are perfect. So when I go to a Four Seasons or a Claridge’s, I understand as long as I’m happy.

ET: If you at one point were going to design your own private jet just for the Santulli Family use, what would be some of the things you would include?

Richard Santulli: I would not do it much differently. We’re actually going to change a lot of our interiors right now. We’re going through a whole process called Next Generation, where we’re working with Colin Cowie and a whole bunch of experts in their fields. We’re going to try and take the quality of everything that touches a customer up a notch. It’s going to take us about three years to do, from how we train our flight attendants, how we train all the service people, how our interiors are going to be changed, how some exterior paint jobs will be changed, as well as our food service. I mean, the whole thing. We’re basically taking a look at everything that touches the customer, and we’ll devote a lot of time, energy and money to take us to the goal. It’s how people use the term “Four Seasons’ service” to mean quality, we similarly want people to say “NetJet’s service” and know it represents the highest standards of quality.

ET: There’s been publicity about the TSA coming up with new security procedures for private jets. What is your thought about this?

Richard Santulli: We work very closely with TSA, DOT and everybody. So far, we have been very satisfied with exactly what the progress has been and how they treat us and we think they listen to us.

Now when they’re talking about certain places where you’re going to have to go through the same security as you would in an airline, that’s going to be expensive for the industry to do. You can’t go to a place like Belmar where they don’t have anything there. So those are the kinds of things we’re working with TSA on. They’re reasonable people; they understand. The scare tactics that some of the politicians made, I just know they’re over-dramatized and overdone.

ET: So you don’t see any dramatically different procedures?

Richard Santulli: No.

ET: What about the battle over fees with the U.S. commercial airlines. The CEOs of the legacy carriers all wrote near identical letters attacking private aviation in their inflight magazines earlier this year.

Richard Santulli: It’s really fascinating. The amazing thing is we spent $50 or $60 million with the airlines last year. That’s just in airline tickets.

If they really look at the situation, they’d see we pay our fair share. General Aviation pays its fair share, absolutely. The airlines are probably a little more concerned that we’re taking some of their business from them but, you know, we have made ourselves very clear, we have written our own letters, and we’ve written them to some of the airlines saying, “Guys, we do buy a lot of tickets from you and we do pay our fair share.” We pay a lot of money in fees. Look, the airlines haven’t done too well.

ET: One could say that the domestic airlines, and the way they’ve treated their premium customers, are probably your best sales force.

Richard Santulli: You said it—I didn’t.

Well, it’s true. Right? If everyone operated like Emirates, we probably wouldn’t have as many passengers. In the airline business, people love airplanes and they think they’re smart enough to run an airline successfully, but they’re wrong. It’s a very difficult business.

ET: For a while you had that relationship with Lufthansa in Europe and that’s dissolved, but do you see opportunities working with commercial airlines?

Richard Santulli: We were disappointed in that because it was a whole big deal. We’re very surprised and disappointed because the deal was such that the marketing was going to be equal, and they just didn’t operate the way we thought they would operate. So, it was an amicable, if you would call it that, split. We think that we’ll probably do another one like that because it worked for them.

It was really supposed to be when a passenger landed in Frankfurt or Munich, they would basically be able to tell their first class and business passengers that Lufthansa went everywhere. But that’s not how it turned out. They were selling point-to-point charter. And we don’t need anybody selling point-to-point charter and not tell us who the customers are.

ET: If you hadn’t started NetJets what would you have done?

Richard Santulli: I like transactions. I’d have my leasing business. I would not be a hedge fund guy. I’m more transaction-oriented, and I can build stuff. It would be my own business and it’d probably be either some private equity but it would’ve definitely been doing deals. But different…different kinds of deals, not plain vanilla stuff. Even when I was at Goldman, I did cross the border leasing in Canada, cross the border leasing in Mexico, a satellite deal…different stuff. Create something and do it.