After significant growth at the start of the 21st century, the past decade has seen the diamond industry shrink, but new figures suggest demand is bouncing back in 2021.

“The diamond industry has no doubt been transformed,” says Edahn Golan, who began his career as a diamond analyst in 2001 and became editor of IDEX online trading platform, and is now an independent analyst.

Golan’s analysis of data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows that, between 2001 and 2007, just under 0.7% of American expenditure was spent on jewelry, with that figure falling to 0.5% in the decade following the global financial crisis. But 2020 and 2021 has seen the first significant uptick in jewelry spending in the 21st century, with figures returning to 2005 levels as Americans spent over $33bn in jewelry stores in 2020.

The first decade of the 21st century saw growing demand for larger and more expensive diamonds alongside the USA’s growing wealth, explains Paul Zimnisky, a New-York based diamond analyst.

But demand has since then fallen as a result of global cultural shifts and changes in supply. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the supply of rough diamonds was restricted, falling to a low of 120 million carats in 2011. This was coupled with huge growth in diamond popularity in the Chinese market which drove up prices, in turn encouraging new exploration and developments of diamond mines.

But towards the end of the 2010s, this resulted in an oversupplied market, reaching around 150 million carats a year in 2017, as fashion trends in the West veered away from larger, more valuable diamonds.

[See also: Azlee Jewelry Reveals Ocean Diamonds Collection]

Research by Golan found that global rough diamond sales fell by 9% between 2010 and 2019, and by as much as a third at some companies. The simultaneous production increase of 14% led to the per carat price of rough diamonds falling by a fifth.

But the last two years have seen growth similar to that seen in other luxury industries, as those with the most disposable income found they had fewer things to spend it on during the pandemic. Instead, they turned to timeless luxuries and recent months have seen rough diamond prices returning to their 2011 levels.

“Right now is kind of the most interesting time for this industry in probably 10 years,” says Zimnisky.

But it’s not just a case of supply and demand, Golan explains. There have been huge shifts in cultural tastes too, especially in the West.

Throughout the 20th century, De Beers dominated the global diamond industry, with its 1940s “A Diamond is Forever” campaign creating a link between diamonds and marriage that remains as indestructible as the stones themselves. To this day, the bridal sector accounts for over half of diamond jewelry sales in the US.

But as De Beers’ domination of the industry waned in favor of other wholesale diamond companies and polished brands, it made less sense to be funneling so much into the marketing of diamonds.

“Once they killed that campaign, it also resulted in the decline in demand for polished diamonds,” Golan says. “But ‘diamond is forever' was so ingrained into the American psyche, it was a slow process to decline.”

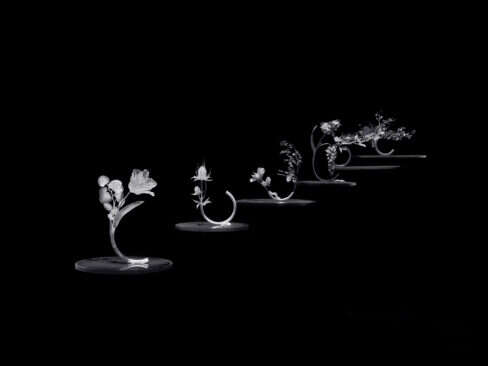

So, Golan says, while the bridal market remains strong, the fashion market for diamond jewelry is transforming, especially over the past decade. A trend towards busier fashion, rather than classic statement pieces, Golan says, has favored designs with smaller diamonds, as well as the use of colors and semi-precious gems.

Noticeable shifts in iconic diamond brands show the way diamonds are adapting to today’s fashion and attract a younger audience. Cartier’s newest collection, Clash De Cartier, in their own words “shakes up the Maison's aesthetic heritage” with punk elements, while Tiffany announced a rebrand in 2018 to appeal to a younger audience with less formal marketing.

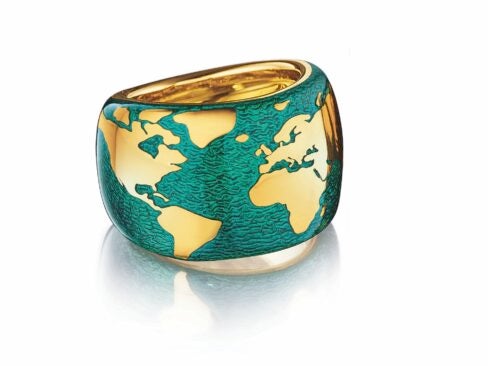

As the traditional diamond target market begins to shrink over the years, major diamond brands need to reposition themselves to match the fashions of the younger generation, as well as meet their ethical and sustainability concerns.

“In the past consumers just wanted the largest solitaire they could get,” Zimnisky says. “Now, consumers want to know where it came from. They want to know it's a real diamond, it’s not a conflict diamond, and it has an interesting story to tell.”