The pitch-perfect notes piercing the crisp morning air outside are so loud and crystal clear that it sounds like the flute sequence from a Puccini opera. Now joined by an equally unrestrained oboe player, my befuddled brain rewinds back to Bhutan’s Paro airport, where I stood in line behind a man whose cap read ‘Oriental Bird Club.’

With the typical duty-free shops and fast-food outlets supplanted by a Buddhist bookshop and photos of beautiful birds, tiny tranquil Paro is more redolent of a museum than an airport. I have, it seems, unwittingly flown straight into Birdwatch Central, but with wonderful wake-up calls like this, that’s not ruffling any feathers.

I eventually arrive at Amankora in Bumthang in central Bhutan, a nine-hour drive along a quiet yak-ruled road with endless loops around massive misty walls of green (70% of Bhutan is covered in forest) as it scythes its way through one of nature’s last remaining unmolested ecological outposts. It’s 50 years since Bhutan, sandwiched precariously between India and China, opened to the world after centuries of isolation, and 20 years since the first international brand appeared.

[See also: Reconnect With Yourself at Six Senses Bhutan]

That was Aman Resorts, after its mythical founder, Adrian Zecha, arrived on the inaugural Bangkok-Paro flight in 1989 with Drukair, Bhutan’s national airline. International carriers still aren’t permitted and, while private jets can land, all pilots must be licensed for Paro’s famously challenging approach. Amankora Bumthang, exuding an understated sophistication long synonymous with Aman, is gently nestled next to an ancient royal palace, the last of five Aman lodges to be constructed, all collectively called Amankora — a model since replicated by other luxury brands.

With its high-value, low-volume approach to tourism, the Land of the Thunder Dragon transmits a seductive siren call to an increasingly over-touristed world. Nearly the size of Switzerland, with less than a tenth of its population, it is rightly terrified of its cultural heritage being irreparably damaged by a rapacious tourist industry. Numbers are kept low by a daily $100 charge, the Sustainable Development Fee, which also helps preserve Bhutan’s unique culture and pristine landscape, as well as supporting free healthcare and education.

In otherworldly Bumthang, inside the 7th-century Jampa Lhankhang temple, the air hangs heavy with centuries of mysticism. Amid the multicolored, timeworn, dimly lit rooms where monks quietly replenish flowers beneath the enigmatic golden gaze of the Buddha, time doesn’t simply stand still; one wonders if it’s ever moved. My guide, Mohan, and I are the only visitors, and while it isn’t quite Seven Years in Tibet, it’s still light-years away from the packed buses and tourist junk plaguing the religious sites of more accessible Buddhist countries. A hundred bucks a day? That’s a bargain.

Mohan reels off a colorful litany of folk tales involving battles between good and evil, crusading heroic lamas, demonesses and consorts capable of assuming other forms, before pointing to a large hole in the stone floor where an evil force once resided. Apparently, evil forces came to feature here regularly. Confused? I know I was, as I stepped circumspectly around the hole, but these rich layered histories interweaving tantric Tibetan Buddhism with long held beliefs in local deities are deeply ingrained and probably best absorbed at one of Bhutan’s many festivals. Mountaineering was prohibited in 2003 precisely because local people deemed it offensive to the spirits who reside there.

A short hike (hiking is as popular as birding) through the forest brings us to the isolated Pema Choling nunnery, where I’m immediately confronted by rows of red-robed young nuns. I expect to be shooed away, but we’re quietly motioned up the corner and served tea, then presented with a large drum full of cookies. Can I take a photo? After a hurried consultation, yes, I can. Then, without warning, they lurch into their incantations and one of my more memorable impromptu travel moments. They all look so trusting, I want to warn them about the evil force of over-tourism. They’ll need more than tea and cookies if that ever breaches the kingdom’s defenses.

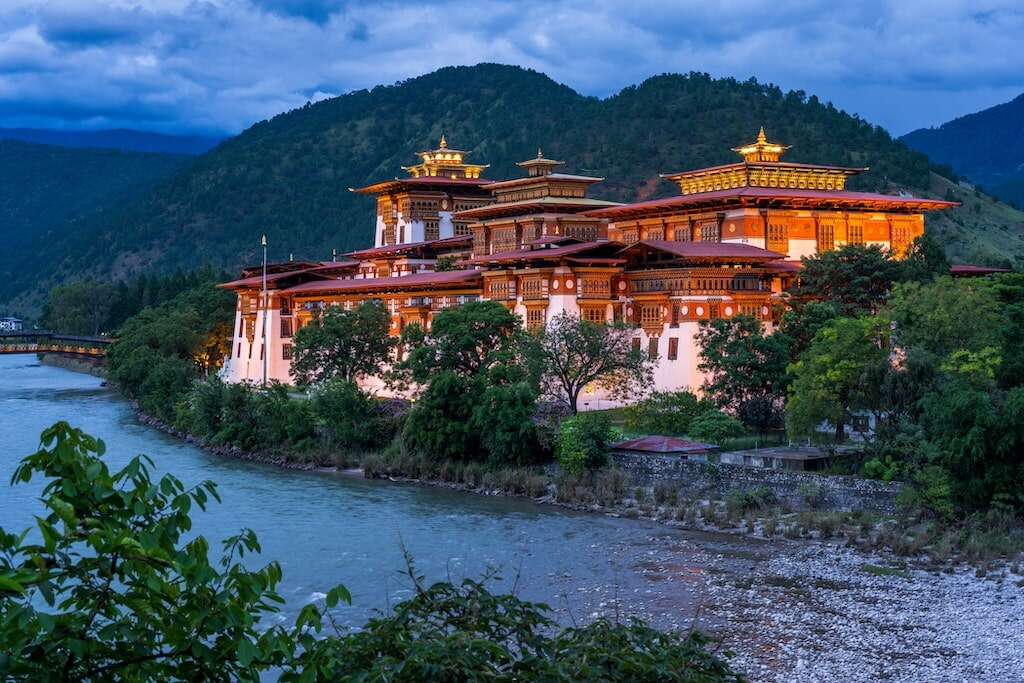

Dotted across Bhutan are the majestic, centuries old dzongs (fortresses), symbols of feudal power in a country that has only existed since the first king was crowned inside the Punakha Dzong in 1907. At the Trongsa Dzong, the largest, I was unbelievably, once again, the only visitor — apart from the monks that live there, one of whom gave me an apple as he showed off his phone.

The luxury lodges of the temperate Punakha Valley, underneath the domineering presence of the dzong, were joined in 2023 by luxury safari specialist andBeyond, unveiling its first Asian property — a sumptuously stylish nine-room lodge facing the Jigme Dorji National Park. The lodge exudes a laid-back opulence underpinned by an elevated standard of cuisine; it proved difficult to say goodbye. The secluded one-bedroom River House, in an idyllic spot next to a tumbling stream, surely rates among the most covetable romantic retreats in the world.

High above Thimphu, meanwhile, secreted among apple orchards across the valley from the Buddha Dordenma (one of the largest sitting Buddhas in the world), Six Senses’ ‘Palace in The Sky’ is, like Amankora, one of five lodges proffering the possibility of an interconnected journey. A modern masterpiece of wood and stone encased in soaring shards of glass, with a large spa next to a fabulous infinity pool, it presides serenely over the capital like a spiritual overlord.

Back down the hill, we find a little town strenuously asserting its credentials as a big grown-up capital city — albeit the only one in the world without a traffic light — where, amid the bustling building work, we stumble straight into an archery contest, Bhutan’s national sport. Two teams, 500-ft apart, all dressed in traditional gho (a knee-length robe), were firing arrows, along with the occasional insult, back and forth from bamboo bows with astonishing accuracy. A highly choreographed song and dance routine was performed every time the target was hit. Accidents, apparently, are not uncommon.

That relationship established by Adrian Zecha between HNW visitors and a unique fragile society wary of being overwhelmed is alive and well. To some, it’s extreme; a sledgehammer to crack a nut, perhaps. But until a better way to safeguard this mesmerizing sliver of Himalayan heaven emerges, just keep on swinging that hammer.