Marine photographer Helen Walne speaks to Elite Traveler’s Kim Ayling about her partnership with Mozambique’s Kisawa Sanctuary.

“I never intended to take up marine photography,” Helen Walne tells me. The South African photographer is a writer by trade and studied art before she discovered, in 2015, a world waiting to be captured below the water’s surface. “After a personal tragedy, I started swimming a lot — mostly in swimming pools, but then I graduated to doing open-water swimming in the ocean. But I was always being left behind because I couldn’t get over what I was seeing beneath me. Everyone else would just use the surface as an exercise place, and I was completely entranced by what I saw below. I decided, ‘Right, I’m not going to swim anymore because I want to just immerse myself in this world.’” From 2017, diving overtook swimming.

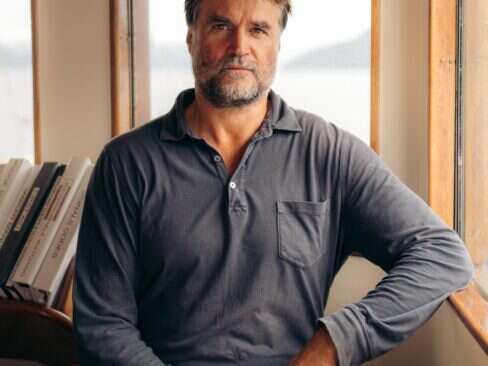

The tragedy she’s speaking of is her brother’s passing; he took his own life in the same spot she dives in daily. “It’s a strange thing because I am drawn to that place and it feels like I am flipping the narrative,” she says. Now, Walne gets out into the water near her Cape Town home every day, camera in tow; she opens our video call apologizing for her damp, tousled hair, fresh from the sea. “I started out taking awful pictures with a really cheap camera, but now I have this enormous rig — it makes me feel very badass,” she laughs.

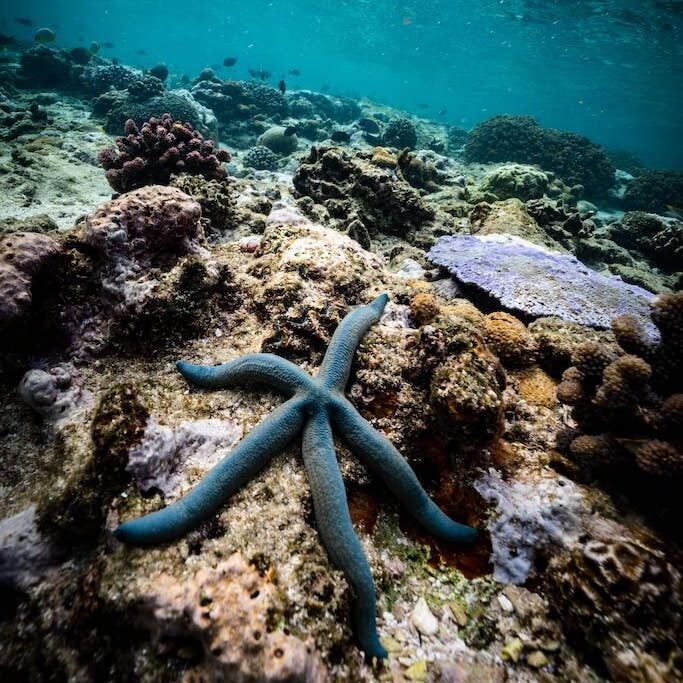

Her work is concerned with the minutiae of underwater life. Instead of sweeping panoramic images of deep-blue sea scenes, hers are a kaleidoscope of color. Yes, there is that famous ocean blue, but also rich reds, browns, pinks and yellows that hone in on weird and wonderful underwater species (a recent obsession was nudibranchs — sea slugs to you and me).

[See also: Laurent Gardinier on the Modern Traveler]

You’ll find her work on her website, but in the contemporary way, it is her Instagram page (with its 24,500 followers) that acts as her real photo journal — to scroll through it is almost to dive with her. “I often think I bring up all of this beauty that most people don’t get to experience,” she says. “People often respond to my Instagram posts, saying, ‘I’m too scared of the water, I can’t dive, but this makes me feel like I’m there.’”

Last summer, though, Walne had a change of scene. In August, she became the first artist in Kisawa Sanctuary’s Island Residencies program — a scheme launched in partnership with the Bazaruto Center for Scientific Studies (BCSS) that invites global creatives to the Mozambique resort with the aim of using art to peel back the layers on its cultural and environmental landscape. “The invitation came out of the blue — at first, I thought it couldn’t be true,” she says.

Kisawa Sanctuary, which opened in 2021, sits on the southern tip of Mozambique’s Benguerra Island in the Mozambique Channel, with its surrounding waters forming part of the vast Indian Ocean. While it is first and foremost a luxury resort, a genuine, meaningful care for the local environment and the people that call it home forms a key part of Kisawa’s identity. Discreetly set among the pristine ocean-front sand dunes, the resort is design-led, using a combination of innovative 3D printing and local artisans to create a sanctuary that has one foot in the future, the other firmly rooted in a more grounded way of life.

[See also: Deborah Calmeyer on Empowerment and Her Pet Lioness]

As part of this aim to exist for the greater good (not just wealthy travelers), the resort hosts BCSS, Africa’s first permanent ocean observatory dedicated to multi-ecosystem time series research. Comprised of a dive center, research laboratory and even on-site accommodation, the observatory operates with the core aim of protecting and preserving local and international marine life. Its research helps guide Kisawa’s everyday environmental decisions — from guest experiences to community outreach projects.

By connecting the resort and its guests with vital scientific research, the partnership has the potential to act as a blueprint for truly sustainable hospitality. “BCSS is such a powerful instrument,” says Walne. “With a lot of high-end places, it can be just ‘profit, profit, profit,’ but [this] marine research center exists because of Kisawa’s funding. It’s an incredible model.”

Despite Mozambique neighboring South Africa, Walne had never been to the country — let alone to the exclusive Kisawa Island. “As a writer and photographer, that kind of place is usually out of my reach financially, so I was really curious. I’ve always been curious about what that part of the world looked like underwater, because you hear so much about coral being affected by climate change.”

[See also: The Best Luxury Hotels With Private Yachts]

What she found, however, exceeded expectations. “It was gorgeous… the sea is the color of — I don’t know! I’ve never seen anything like it — pure turquoise,” she exclaims. As part of its resort-to-research collaboration with BCSS, Kisawa has used novel 3D seabed mapping to create virtual reviews of each of its 13 nearby dive sites, each with thorough accounts of depth, visibility and common resident species. “Our guide took us to Two Mile Reef, which is one of the main reefs. It was busy with tourist boats, but those corals really rival what you can see around the Red Sea — they are pristine and thriving and rich. It was amazing.”

Despite being catapulted to virtually the definition of paradise, heading around the South African coast, east toward Mozambique, presented new challenges for Walne — namely, her subject. Back in Cape Town, kelp forests work to her advantage, creating funnels of light to frame the marine life within; Benguerra Island’s coral, not so much. “Coral is so much harder to photograph. It’s just very… there,” she says. “It’s way more challenging but it’s really helped me to understand how it works as a creative medium — I want to do a coral series now.”

[See also: Waldorf Astoria Seychelles Platte Island Welcomes First Guests]

As you’d expect, spending so much of her life among the species and inside the water has spurred on Walne’s steadfast commitment to helping protect them — not just via partnering with brands and organizations with the motivation and the means to make a difference, but also through her art itself. “Animals and plants, they don’t speak ‘human,’ so I see myself as a bit of a conduit. And maybe I’m not always saying the right thing… but it’s almost like I am collaborating with them to show people how fragile things are,” she says.

“The way I take pictures is to capture beauty, and I really hope it moves people. And then once they get invested, then they realize we have to look after this [environment] because — particularly corals, but even kelp — they are really suffering.”

What began for Walne as a form of therapy following the loss of her brother has taken on a life of its own, melding into more than just a passion project but a global career in a field she never anticipated. “It’s evolved — in the beginning, it was definitely a healing experience. But now it’s something beautiful and more a joyous celebration. I don’t think I would have ever started swimming or diving without that.”