Most ballerinas begin as small children, smitten with a desire to dance, or coaxed into classes by parents. But tutus and ballet shoes weren’t part of Misty Copeland’s early life.

The first African American woman promoted to principal ballerina at the American Ballet Theatre (ABT), Copeland didn’t take a single dance class until she was 13 years old, when she was encouraged by a local trainer. It would change her life, and the lives of others, forever.

“I often say that ballet found me,” says Copeland, explaining that, when she was growing up in California, she went to the Boys & Girls Club when her mother was working. A ballet teacher approached Copeland, convincing her to take a class.

“It was the first time I was part of any organized sport or the arts,” says Copeland. “I needed to be pushed, and I needed someone to believe in me because I wasn’t getting that at home.”

[See also: The Women Making Waves in Luxury Design]

Those first classes taken at the age of 13 were freeing for her: “I fell in love with the escape from the circumstances that were my life. Not often having a home and being very poor, I was in survival mode all of the time, and this was a place where I could put my focus on something that was beautiful.”

She trained intensely after that, and it was almost immediately observed that she was a true prodigy. By age 14 she was performing, and at 15 she was winning awards. Those teenage years, though, were challenging.

Copeland lived with her trainer as her host for several years, had a confusing relationship with her mother at times, and moved around to join classes, perform and attend workshops. She also struggled with the fact that she was a black woman in a predominantly white ballet world, making it incredibly challenging to rise through the ranks.

“I remember having to put lighter makeup on my face to blend in with the rest of the ballet,” recalls Copeland. “That’s when I realized that I needed to find support. I had never really reached out and asked for advice or support, and it took me the long route to get to where I needed to go.

“I value the time that I am in the studio or on the stage, and how rich and meaningful that is. I don’t take it for granted”

“I think I was 17 years old when I really came to terms with myself as a young adult, and my eyes were completely opened to the lack of diversity in ballet. I didn’t really have anyone who had done it before to show me the ropes, and I realized then that I needed to find a way to carve my own path. I learned a lesson from that. Today it is interesting to look back on all those years without seeing another black girl come to the American Ballet Theatre.”

While there had been African American ballet dancers before her — including two females who had been principal dancers with other companies years earlier — from 2008 onward, she was the only African American woman in ABT throughout her career.

“I feel so grateful for my manager, that she saw this bigger vision and purpose for me,” says Copeland. “She introduced me to ballet in a way that it could be usable; it transcends so many generations of people. My personal story — being a black woman who had a positive and successful experience coming from where I came from — that positive story carries an impact. I feel it has opened the door for more representation in this art form. We are bringing ballet to a broader audience and getting more diversity in the field. There was a lot of work for many years before we saw that shift happen, but now it seems attainable.”

[See also: A Day in the Life of Martin Brudnizki]

In fact, Copeland recalls a pivotal moment in ballet for her, the time she realized she was making a difference. It was in the Firebird performance in New York City at the Metropolitan Opera House during ABT’s spring season in 2012.

“We worked so hard to reach the black community, and I remember the moment before I went onto the stage, looking out at the audience and seeing how many people turned out. More than half were black, and I had never seen that before. When I went onto the stage, they were screaming and cheering so loudly that I couldn’t hear the orchestra. I had no idea what was happening with the music. I was feeling an overwhelming sense of pride, not about me, but about what I represented.

“So many generations of black women weren’t given the opportunity to be in this position, and the possibility for future generations was there. It felt like the longest amount of time,” says Copeland, who says her ensuing intense stare at the conductor gave her a sense of where the music was, and she was able to get back into the ballet moment.

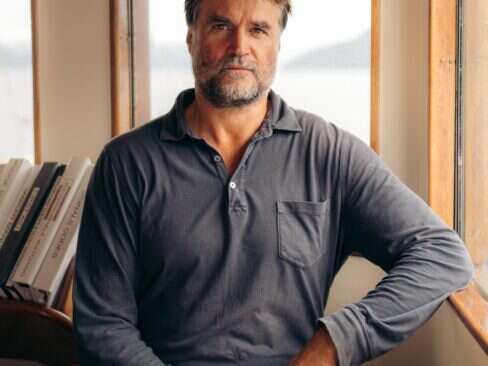

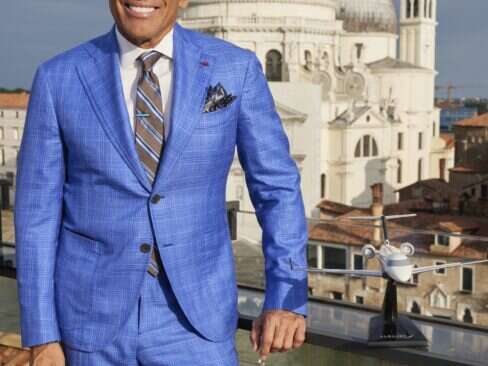

Just last year, Misty Copeland was named to Swiss watch brand Breitling’s Spotlight Squad / ©Breitling

Copeland’s career soared from 2007 onward, and she became an important name and a respected figure for black women around the world. The year 2015 was crucial for her; it was the year that the documentary about her life, A Ballerina’s Tale, made its debut (with her in the starring role). It was the year she was named to Time magazine’s “100 Most Influential People” list (with Olympic medalist Nadia Comaneci positively referring to the unrelenting Copeland as a “badass.”), and it was the year she was promoted to principal ballerina at ABT — making an unparalleled statement about diversity.

Today, the trailblazing Copeland still lights the way when it comes to making a difference. Just last year, she was named to Swiss watch brand Breitling’s Spotlight Squad. Breitling brings brand ambassadors together in the form of ‘squads,’ whose members work together to promote different causes. The Spotlight Squad is about women and the difference they are making when it comes to empowerment and diversity. Copeland is joined on that team by Yao Chen and Charlize Theron.

“It’s been amazing to have these opportunities to reach new audiences and to come together with other powerful women,” says Copeland. “The impact is much greater as a team, and it is the right time to come out to show support for other women who share the same goals of women having more strength, grace and a voice.”

[See also: Beth Novak Milliken on Inspiring Change in Napa Valley]

It takes time to be strong enough to fly through the air gracefully, to tell a story through movement and music. “I value the time that I am in the studio or on the stage, and how rich and meaningful that is. I don’t take it for granted,” says Copeland. “It takes a lot of training and strength to be part of something that is beautiful and moving. It takes incredible vision and deep attention to the music to create this beautiful illusion. It’s like we are these superhuman beings who can defy gravity and make it seem effortless, but there is so much work going on underneath.”

Still at the height of her highly successful career, Copeland nonetheless marches on as an innovative leader. This past year, she founded Swans for Relief as a GoFundMe fundraising effort to help dancers who were out of work and in need due to the pandemic. In addition to working on another book, she also has her own production company (started with a friend about five years ago) and is focusing on a way to tell women’s and immigrants’ stories in an authentic way, expressed by people who have experienced hardships and successes.

“From here, it is all about using my voice, my reach and my art to spread out like branches of a tree in so many ways to be able to be representative of black women for generations to come.”