Picture a glass of champagne, the tiny streaming bubbles giving the wine a unique shimmer and sparkle. That famous effervescence is why everyone pours it for celebrations and romantic dinners. Bubbles seem to make us and our lives sparkle too. So it may seem surprising that the region’s latest trend is making wines without that trademark fizz.

But climate change, which is upending many wine traditions, is behind a rush of new still-wine projects. Grandes marques Louis Roederer and Charles Heidsieck have debuted bubble-free chardonnays and pinot noirs, the region’s main grapes, as have cult grower producers Jacques Lassaigne and Marie Courtin.

Grower Benoît Déhu released several micro-cuvées from red Meunier grapes, while Drappier’s Trop m’en Faut white is Pinot Gris. The official label term for these wines? Coteaux Champenois.

[See also: Telmont’s Ludovic du Plessis on Bold Ambitions for a Green Future]

Long ago, all the chilly region’s wines were no-fizz, but they often weren’t successful. Some years were too cold to fully ripen the grapes and give the wines sufficient flavor concentration. The discovery of how to put bubbles in the bottle — adding sugar and yeast so the wine ferments a second time — was a godsend.

It transformed tart, acidic wines into a more palatable style. Blending different grape varieties and vintages helped.

Still wines were quickly sidelined, except in the village of Bouzy and area of Rosé des Riceys, whose pink wines were appreciated by Louis XIV. The few modern trailblazers included Bollinger’s red La Côte aux Enfants, around since 1934.

[See also: Crurated Launches Blockchain-backed Virtual Wine Cellar]

Then, over the past two decades, came climate change. The temperature in Champagne has risen around 2° Fahrenheit in that time — grapes ripen earlier and better, and winemakers started experimenting. One of them is Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon, chef de cave at Louis Roederer (maker of Cristal), who observed that his shift to organic and biodynamic farming, plus climate change, produced riper fruit with the emphatic flavors expected in still wines.

After replanting a few special plots with vines from Burgundy, he let grapes get riper than he would for sparkling wines. With the 2018 vintage, he was finally happy enough to release the first two.

You might expect all these wines to resemble red and white burgundies, but they have their own style: lighter, tangier, more lively and vivid, with less richness. They’re expensive, but delicious.

[See also: Martell Releases World’s Most Expensive Cognac]

Most producers now make at least one, says Peter Liem, author of Champagne: The Essential Guide to the Wines, Producers, and Terroirs of the Iconic Region. And as the climate keeps changing, there will be even more.

Take Two // Coteaux Champenois

2019 Louis Roederer Hommage À Camille Blanc Coteaux Champenois

The second vintage of chardonnay in Roederer’s collection of still wines is stunning, with lemon and hazelnut aromas, shimmering citrus and chalk flavors, and a lush texture. It’s from a tiny plot in the Les Volibarts vineyard, and named for Camille Olry-Roederer, who ran the Maison from 1932 to 1975. $200, louis-roederer.com

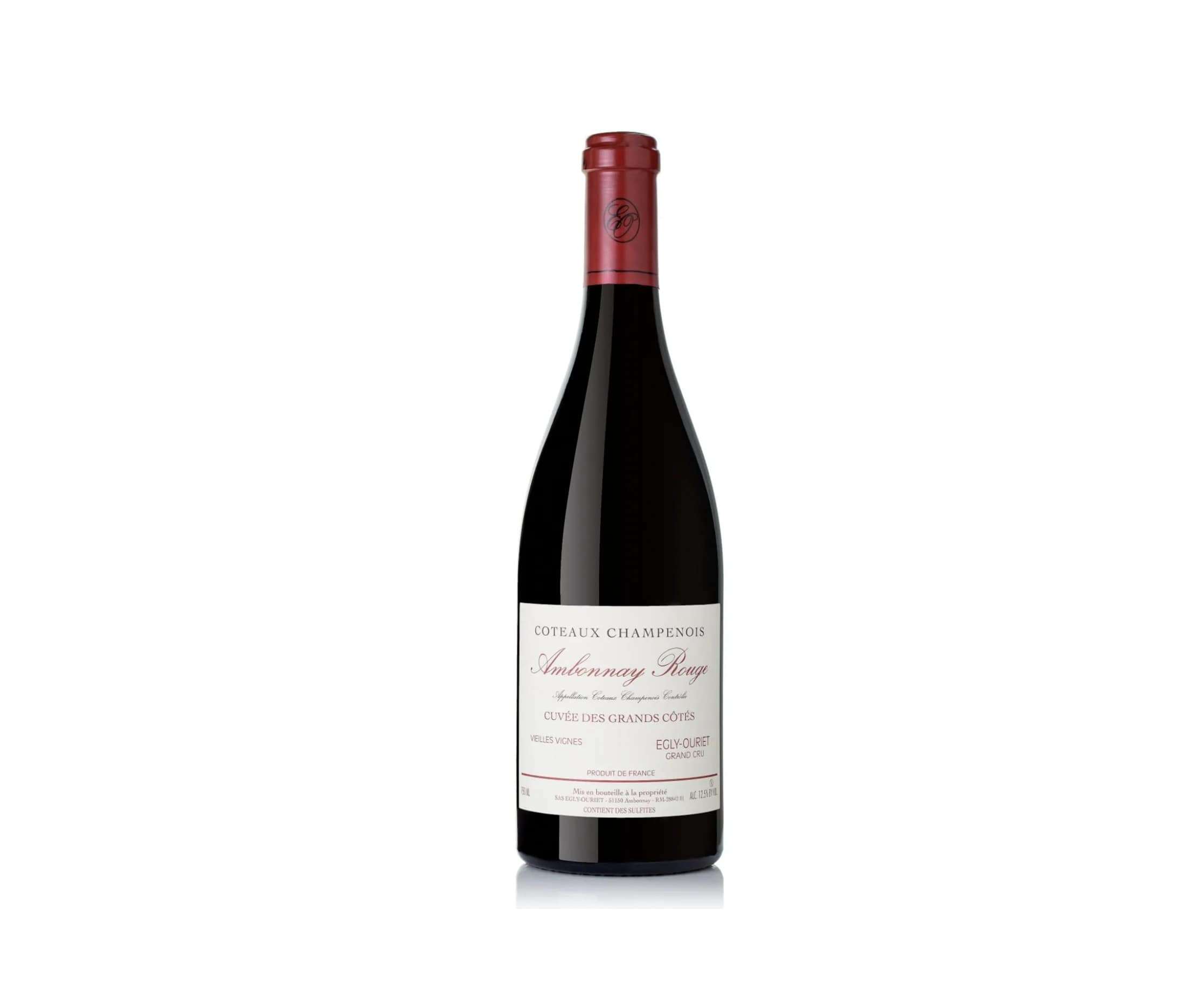

2020 Egly-ouriet Ambonnay Rouge Coteaux Champenois Cuvée Des Grands Côtés

This family-run organic grower-producer is a still-wine trailblazer. For decades it has made this superb pinot noir from old vines in grand cru vineyards in Ambonnay. This vintage brims with rose petal and spice aromas and berry and mineral flavors and has a silky, velvet-like texture. $325, skurnikwines.com