When Patek Philippe set out its stall at Watches and Wonders in April, much attention was paid to a new Nautilus with a white-gold case, a blue-gray dial and an unusually casual denim-inspired strap. The sports watch remains Patek’s most popular timepiece, with some customers waiting upwards of 10 years from order to delivery. As crowds gathered around this usual suspect, the Swiss brand quietly launched a showstopping product 15 years in the making – and it doesn’t even keep the time.

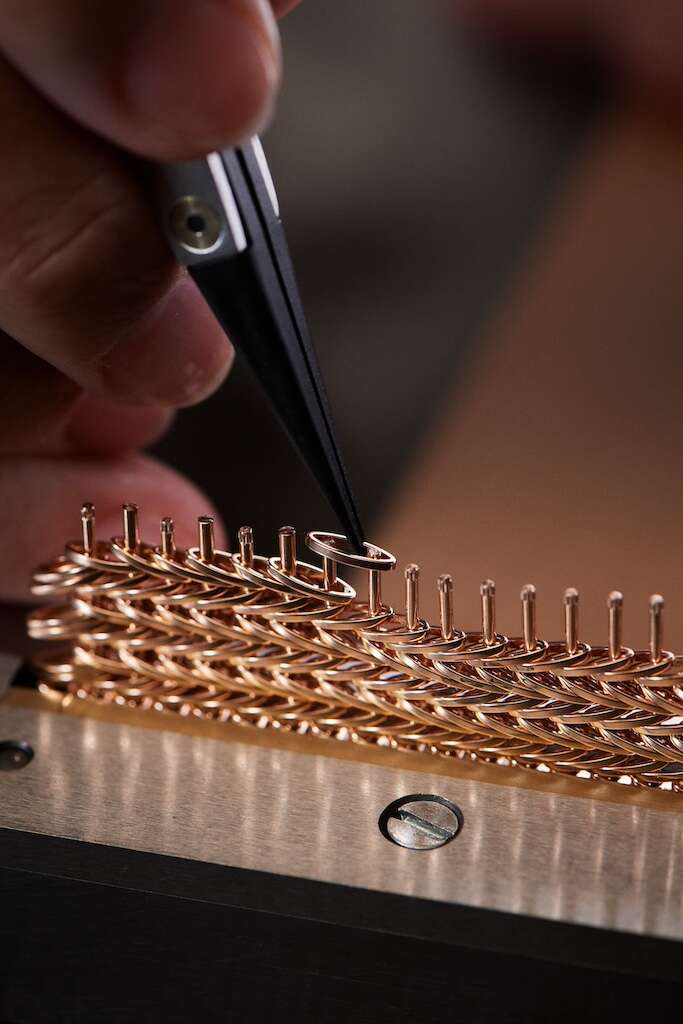

On the face of it, a new chain bracelet, presented on an otherwise unchanged preexisting model, may struggle to inspire. But the level of craftsmanship and exact timing of its unveiling display the watchmaker’s uncanny ability to predict trends and innovate accordingly. In true Patek fashion, this is no normal bracelet. Comprised of 363 parts, including over 300 individually hand-polished 18-karat rose gold links, it is one of the most intricate watch bracelets ever released. The bracelet’s gold links are first produced by machine before being polished and assembled one by one by chainsmiths.

[See also: Behind the Scenes with the Man Behind Dom Pérignon]

Although visually stunning, the design is as functional as it is stylish and addresses fundamental issues with chain bracelets. Popular in the 1960s and 1970s, even the best bracelets were inflexible, leaving them uncomfortable to wear and prone to snapping. They were also difficult to adjust and often seen dangling, precariously loose, on wrists at cocktail parties. Impractical for both watchmakers and wearers, they inevitably fell out of fashion.

“Classic chain bracelets from the 1960s and 1970s, with their links crafted one by one by artisan chainsmiths from a gold wire and then assembled by hand, were appreciated for their remarkable suppleness and creativity,” Jasmina Steele, communications director at Patek Philippe, told Elite Traveler.

“The main challenge with these beautiful traditional chain bracelets was that the adjustment of the length of the bracelet had to be done at the point of sale by a jeweler and, once cut-reduced in size, it could not be readapted to a larger size. Consequently, the bracelet had to be replaced.

“Some of the chain bracelets were also fragile, and repairing was quite difficult if not impossible without a repair that would be visible. Finally, in time, many points of sale no longer had on-site jewelers, so the sizing of the bracelet became difficult or just not possible upon purchase.”

[See also: The Elite Traveler Edit of the Top Watches of 2024]

In Patek’s patented design, the links move independently from one another, making it more flexible and more comfortable. To address the fundamental issues around the fit, its chainsmiths have innovated a new clasp with three different adjustment notches, giving wearers a much closer fit without the need to take it back to the jeweler.

This new bracelet took the best part of two decades to develop, so you would assume such an investment would go into the manufacturer’s most popular models, but it has instead been given exclusively to one of its most under-appreciated: the Golden Ellipse.

First launched in 1968, this mid-century-inspired dress watch stood in stark contrast to designs of the time. Not much has changed 56 years later. It still has the same not-quite-a-rectangle but not-quite-a-circle case and a hyper-minimalist dial. It still stands out in a sea of right-angled dress watches.

While this new release – Reference 5738/1R-001 – represents something of a relaunch for the Golden Ellipse, it has been ever-present in Patek’s collection since its unveiling (albeit firmly in the shadow of the Nautilus and its sportier cousin, the Aquanaut).

But mid-century dress watches are back in vogue, with vintage Cartier Tanks and Jaeger-LeCoultre Reversos experiencing an explosion in popularity. Still, Steele believes vintage dress watches would be even more popular with younger consumers had the issue around chain bracelet sizing been solved earlier.

She said: “The new chain-style bracelet is the perfect aesthetic association going back to the original Golden Ellipse models of the 1960s. Many younger-generation customers appreciate the design period but have to refrain from considering the vintage original chain bracelet models, because of the bracelet sizing problem and, in most cases, it is no longer possible to re-create the original chain bracelet.”

[See also: Wiesmann Project Thunderball: A Classic Redefined]

The watch’s ‘sunburst’ ebony black dial, and baton-style hour markers and slim hands (both in rose gold), complement the bracelet and case and reflect that classic mid-century mix of black and gold. The movement, an ultra-thin 240 caliber, is another unsung hero. The self-winding movement with a 48-hour power reserve remains largely unchanged from the one that debuted in the original Golden Ellipse in 1968. It measures just 2.53mm thick, giving the watch an overall depth of 5.9mm – that’s the thinnest Patek in its continuous collection.

It’s not on par with some of the ultra-thin watches we saw at Watches and Wonders (Bulgari set a world record with its 1.7mm Octo Finissimo Ultra COSC), but it nonetheless remains at the forefront of watch technology almost 60 years after its development.

“Creating and producing elegant slim watches is a key design rule of Patek Philippe watches,” Steele said. “The self-winding Caliber 240 is a strong movement, it can drive additional functions and complications, and it is reliable over the long term. It’s what we call a ‘no-problem’ caliber. It is beautiful, and it has proved its dependability over time.”

From $60,100, patek.com

[See also: How Montblanc Creates the World’s Finest Pens]